The Church Sanctifying:

Sacraments of Membership

Return to

Index The Catholic Faith

Return To

Level Four Topic Index

Home Page

"And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son of the Father. And from his fullness have we all received, grace upon grace" (Jn 1:14, 16).

To help us understand the Church's role in the dispensation of grace let us consider for a moment the parable of the Good Samaritan. You may already be familiar with this parable, but we will look at it in a slightly different light.

A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him and departed, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he journeyed, came to where he was; and when he saw him, he had compassion, and went to him and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; then he set him on his own beast and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. And the next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper, saying, "Take care of him; whatever you spend, I will repay you when I come back" (Luke 10:30-35).

We know that Our Lord told this parable in answer to a question about who is our neighbor. This parable teaches us a lesson about real charity. However, it seems that Our Lord also had a deeper message in mind about grace and the sacraments. As the fourth-century bishop St. Augustine explained in one of his sermons, this parable teaches us about our salvation.

Let us suppose that the man who is traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho is Adam, who also represents the whole human race. He was "robbed" - by the devil - of his riches, that is, the life of grace. Just as the man was left half-dead by the side of the road, the human race is weak, fallen, and without the many gifts God intended for us. Most important, after the Fall we were unable to attain salvation. The priest and the Levite signify the priests and the prophets of the Old Covenant, who were unable to restore us to supernatural life. Finally, the Samaritan pouring oil and wine on the man's wounds represents Christ, who "Pours out" graces through the sacraments to heal our spiritual wounds.

Sacraments of Initiation

The main purpose of all the sacraments is to give us grace and bring us to salvation. However, three of these sacraments are also important to our life as members of the Church. In fact, Baptism, Holy Eucharist, and Confirmation are the sacraments by which we are fully incorporated into the Body of Christ. These sacraments are sometimes called sacraments of initiation, since they bring us into the Church and give us full participation in her. They also signify our unity in the Body of Christ.

Baptism

Baptism is the sacrament that frees us from original sin and fills us with divine life - sanctifying grace. We receive the Holy Spirit, who then lives in us. It makes us children of God and heirs to the Kingdom of Heaven. This sacrament unites us with Christ in a special way, giving us an invisible seal, or mark, which can never be taken away.

Yet the effect of Baptism goes far beyond our own personal lives. Baptism makes us members of the Mystical Body of Christ. In St. Paul's letter to the Corinthians he tells us, "For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body . . . and all were made to drink of the one Spirit" (1 Cor 12:13). So Baptism makes us members of the Church and unites us closely with all those who have been baptized in Christ.

Baptism is also the gateway to all the other sacraments. Once we have become part of the Church we are able to receive from her the graces dispensed through the other sacraments.

The Eucharist

The next sacrament is the Eucharist, which in itself is the most important of the sacraments. First of all, it is a source of spiritual food. This aspect of the Eucharist was prefigured in many ways in the Old Testament - for example, when the manna in the desert nourished the Israelites for many years. In the New Testament, after the multiplication of the loaves and the fishes, Our Lord spoke to his disciples about the "Bread of Life":

Jesus said to them, "I am the Bread of Life; he who comes to me shall not hunger, and he who believes in me shall never thirst. . . Your fathers ate manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the Bread which comes down from Heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. I am the living Bread which comes down from Heaven; if any one eats of this Bread, he will live for ever; and the Bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my Flesh. . .Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat of the Flesh of the Son of Man and drink his Blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my Flesh and drinks my Blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day": (Jn 6:35, 49-51, 53-54).

Our Lord tells us here of the necessity to nourish the life of grace born in us through Baptism. Just as our bodies require nourishment, we must "feed" on the life of grace through reception of the Eucharist, the Flesh and Blood of which Our Lord speaks.

Furthermore, the sacrament of the Eucharist is both a cause and a sign of the unity of the Church. The Eucharist causes first our union with Christ and through him our union with one another. All those who receive Christ are truly united through this sacrament. St. Paul affirms this also, in his letter to the Corinthians, when he says, "Because there is one Bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one Bread" (1 Cor 10:17). It is this union with Christ and his Body that is signified by the words Holy Communion.

Even the elements of bread and wine chosen by Our Lord for this sacrament signify the very unity that it brings about. Just as many grains of wheat make up the one loaf of bread, and many grapes produce the one cup of wine, so too many Christians are joined into the one Body of Christ through the Eucharist.

Confirmation

The third sacrament of initiation is Confirmation. Confirmation is the sacrament in which we receive the fullness of the Holy Spirit. This enables us to profess our faith as strong and perfect Christians and soldiers of Jesus Christ.

Although we receive the Holy Spirit at Baptism, Confirmation completes what is begun in Baptism and has been nourished through the Eucharist. The new life of grace that we receive, usually as infants, is strengthened in us at Confirmation. At Baptism we were spiritual infants in the Church; at confirmation we become spiritual adults.

We know from our experience that, as we grow older, we take on more and more responsibilities. When we are an adult, we have to bear the responsibilities of citizenship - voting, paying taxes, and perhaps fighting to defend our country.

The same is true in the Church. As adult Christians we have the responsibility to bear witness to Christ. This means that we must live for Christ in our daily lives, defend Christ and our faith when it is challenged, and perhaps even die as martyrs. The graces of Confirmation prepare us to meet these challenges.

The notion of defending our faith has led many of the Church Fathers to speak of Confirmation making us soldiers of Christ. St. Paul uses this idea when he writes to the Christians in Ephesus, encouraging them to be strong in their faith:

Therefore take the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand. Stand therefore, having girded your loins with truth and having put on the breastplate of righteousness; . . . above all, taking the shield of faith with which you can quench all the flaming darts of the evil one. And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God (Eph 6:13-14, 16-17).

We must pray then that we use the gift of the Holy Spirit to strengthen and defend our faith always.

As members of the Mystical Body united through these sacraments we have obligations to live as part of Christ's Church. We must accept the teachings of the Church and follow the laws that she has wisely set down.

We must also continuously strengthen our faith through reading and instruction. We know that Confirmation is usually preceded by an intense period of instruction preparing us for our place as adult Christians. However, growth in knowledge and understanding of our faith should not end here. Just as most of us continue our secular education in an informal way after completing school, we must continue our education in our faith. We must strive to deepen our understanding so that we may draw closer to God and our eternal goal.

Rites in the Church

With these three sacraments comes full membership in the Church. But the way the sacraments are celebrated may vary. This is because the Catholic Church is composed of various rites. Here a rite refers to a common way of worship and of practicing the faith by a particular group of Catholics.

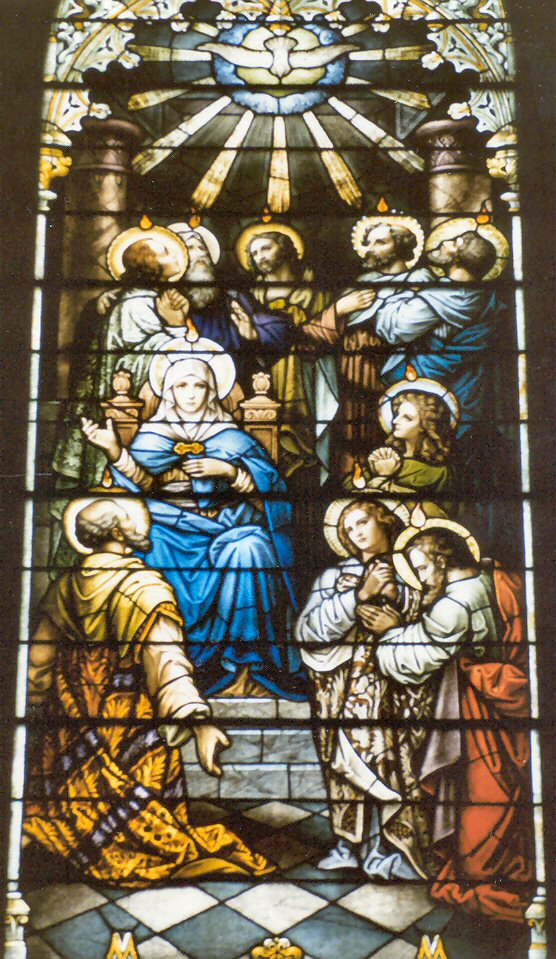

These rites are ancient in origin, and all of them can be traced back, in some way, to the days of the apostles. When the apostles set out to "teach all nations", they had received the Holy Spirit and were well-grounded in the doctrines of the faith. But they had not yet settled on the precise forms for the various ceremonies. In fact, these ceremonies developed over a long period of time and reflected the cultures, languages, and history of the various places where the gospel was preached.

As the Church grew, each bishop celebrated Mass and administered the sacraments according to the customs of the city where he lived. Certain cities eventually exercised more influence that others in the surrounding countryside. Of course, Rome, as the center of both the Roman Empire and the Church itself, was the most important. Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul in Turkey) was the center of the eastern half of the empire and became quite important too.

In the Church today there are several different rites. The largest of these - and the one with which you are probably most familiar - is the Roman rite, which is used throughout the Western world. It is called "Roman" because the ceremonies originally come from the diocese of Rome. The second-largest rite is the Byzantine rite. This rite comes from the ceremonies of the church in the city of Byzantium, or Constantinople - the eastern part of the old Roman Empire. There are also several smaller rites whose origins can be found in other Eastern parts of the world.

These rites are all united under Christ and his Vicar on earth - the Pope. All who belong to them are members of the Catholic Church. The fundamental beliefs are the same, but the expression of those beliefs and the ceremonies vary according to the different cultural origins. To help us understand, let us look at a few differences between the Roman rite and the Byzantine rite.

In the Roman rite, unleavened bread is used for the Eucharist, while Byzantine Catholics use leavened bread. While Roman rite Catholics traditionally genuflect before the Blessed Sacrament, Byzantine rite Catholics have always bowed as a sign of respect. Members of the Roman rite make the Sign of the Cross from left to right; members of the Byzantine rite do so from right to left. The churches of the Byzantine rite are decorated with icons, flat paintings of Our Lord, Our Lady, or the saints, often done on wood and decorated with gold and jewels. The churches of the Roman rite often contain statues in addition to other kinds of images. You will not usually find statues in a Byzantine church.

As you can see, the differences are not in essential beliefs. Both reverence the Eucharist as the Body and Blood of Christ, even though respect is shown to this great sacrament in different ways. This variety enriches the Church, but it also points back to its unity, since all are part of one Church.

Used with the permission of The Ignatius Press 800-799-5534

Return to

Index The Catholic Faith

Return To

Level Four Topic Index

Top

Home Page